Note: This essay is extremely spoiler heavy for the newest Ari Aster film, Beau Is Afraid. I genuinely think the film is best viewed with as little prior knowledge as possible. If you’ve yet to see Beau, I humbly request you bookmark this page, go watch it, and come back when you’re done. There is no doubt Beau is long and divisive but if you go into it with a curious attitude and let Ari Aster’s opus wash over you, I’m confident you’ll have a good time.

So if you’re still reading now I’m gonna assume you’ve seen the film. In which case, let us take a moment to decompress together — what the fuck, right? If Beau made you feel confused and left with you numerous lingering questions and uncertainties then I am right there with you. I will not pretend to fully understand or even “get” Beau. I have no interest in reading nor writing some “explainer” essay attempting to literalise every facet of the film until the story curves to fit some tortured metaphor or allegory.

In my view the film is highly illogical and set in a ludicrous reality, seeking sense in it is to me a fool’s errand. This does not one bit inhibit my enjoyment of the film. If anything, Beau’s abundant absurdity is what made it my most enjoyable theatrical viewing experience in a long time.

I’ll give you an example of what I mean, at one point during the film –– having already witnessed Joaquin Phoenix unwittingly forfeit his apartment to a throng of street urchins for the night, learn of the death of his mother (a chandelier crushed her head), sprint through the street naked, get hit by a car and then repeatedly stabbed, wake up in the house of a strange family who quasi adopt him/place him under house arrest, and ultimately break free from the family, leaving a teenage girl’s suicide in his wake –– I looked down at my watch and realised the film still had the guts of two hours to go.

What I mean to say is, Beau was lengthy but also utterly unpredictable. Just as I had wrapped my head around one strange scenario another one came into view. Not only was it absurd but it was also grand in scope. Reminiscent of Homer’s Odyssey, Beau’s voyage is exhausting and unrelenting. The best I could do was succumb to the film, brush aside any questions I might have had and let the story consume me.

And so I did.

And I also laughed my ass off.

I laughed and laughed and stared up at the screen with a big goofy grin on my face for the film’s entire length. I laughed when the teenage girl chugged a tin of paint, when a chronically grieving Beau watches a play and the curtains open to reveal two headstones labelled MOTHER and FATHER, when his mother (who’s face we’ve been told was utterly pulverised by a falling chandelier) has an open casket funeral, her headless body beautifully presented with all the associated pomp.

To me, the film was an utter laugh riot. (An opinion sadly not shared by the three other audience members at my screening whom remained resolutely quiet for the duration, apologies to them for my disturbance.)

The thing is, I know exactly why Aster’s humour resonated so deeply with me, it’s because it bares both superficial and fundamental similarities to the maximalist absurdist comedy of my favourite improv troupe, Big Grande.

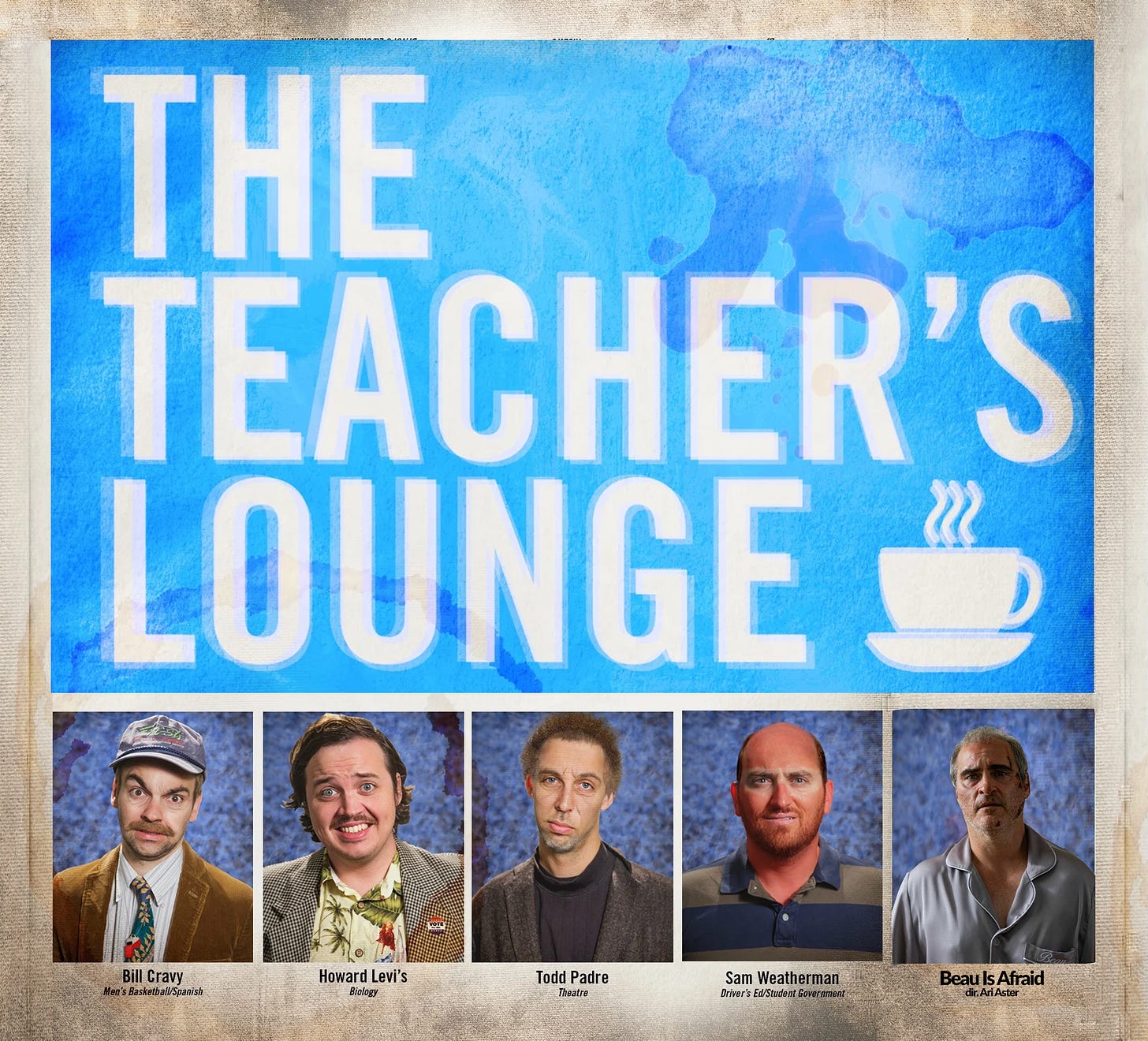

For the unaware, Big Grande are a four person improv group made up of comedians Dan Lippert, Jon Mackey, Ryan Rosenberg and Drew Tarver. Best known for their cult favourite podcast “The Teacher’s Lounge”, they also collaborate on a number of other projects and frequently perform live (I highly recommend checking out their filmed live shows Live On Set).

On The Teacher’s Lounge, Big Grande introduce a banal reality (a high school teacher’s lounge) and rapidly elevate their characters’ circumstances and biographies to profoundly absurd ends. The first season, six episodes in length, culminates with the teachers blowing up the school, being raided by the FBI and escaping in OJ Simpson’s famous white Bronco.

Future seasons saw the slate virtually wiped clean with the teachers going on to establish their own private school (which quickly became a de facto nation state), move to LA, open their own shopping mall and literally go to hell.

What sets Big Grande apart from other improv groups is their almost adversarial methods of escalation within a scene. Whilst one member speaks in a scene, there are three lions listening carefully, ready and willing to pounce on every flub or slip of the tongue and “yes and” the unintended inference, forcing the speaker to defend the new reality hastily built around them.

One textbook example of this is can be found when Drew Tarver misspoke when saying the word “fajitas” and the others jumped into agree that yes, the school canteen were indeed serving “fa-feetas” and made it clear to the audience that they were made with real human feet. This sparked a long running gag and introduced the concept of cannibalism to the Teacher’s Lounge universe which in later seasons would become a recurring motif.

This is just one way listing to Big Grande and watching Beau Is Afraid felt similar for me. Just as Lippert, Mackey, Rosenberg and Tarver quickly foist new realities upon the listener that routinely break societal and even physical norms (a favourite bit of mine which saw three of the Teachers infiltrating a school dance disguised as a 1. A man with a top hat and moustache, 2. A fridge and 3. A glass of water (from which the man was sipping) is just one example of Big Grande forcing physics to bend to their whim) is in my view, heavily reminiscent to how Aster efficiently establishes and then disregards sequences in Beau at a breakneck pace.

Both Lounge and Beau play fast and loose with logic and reasoning. Take for instance when Beau discovers a TV channel monitoring his every move. At first it appears to be just closed circuit TV, he can even see the camera filming him. But when he presses fast forward on the remote, he catches glimpses of his future and the camera is no longer diegetic but an all seeing “God-cam”. None of this is ever explained.

Or consider all the fake band and movie posters hanging in the teen girl’s bedroom he awakes in after his car-accident-cum-stabbing. They wouldn’t be worth pointing out in isolation but when compared to the girl’s brother’s room which is adorned with real life posters of real life bands, the dichotomy between the two sets raises a lot of questions (all of which go unanswered within the body of the film).

And then there’s the different environments Beau traverses through, each as intricately built as the last and full of lived in characters but which are unceremoniously dumped before much can be learned of them. Take Beau’s street for example. That setting is incredibly well realized in terms of geography and character, very quickly establishing a “Barton Fink meets Taxi Driver” vibe. It is also informative of a wider reality. But that reality (a crime riddled, seedy, dog-eat-dog America devoid of “law and order” is never again touched upon within the film. Nor is the suburban-home-slash-asylum or the forest theatre people’s hippie cult.

Each setting feels whole cloth distinct from the others, almost like a video game protagonist graduating through new levels. As a long time Teacher’s Lounge fan, I couldn’t help but equate these episodes in Beau’s life with seasons of the show. Like the teachers – doomed to walk the earth (and afterlife) as failures, enduring humiliation after humiliation in increasingly preposterous situations – Beau is transplanted into new environs and is endlessly put upon and challenged, the man can’t even take a bath in his already flooded apartment in peace for crying out loud!

It must also be said that many of Beau’s gags and plot points would feel right at home in a Teacher’s Lounge season. A paranoid middle aged man, from an unfathomably wealthy family living a lonely, destitute life, convinced by his business magnate mother that he will die upon reaching orgasm is a totally plausible backstory for Mackey’s “Howard Levi’s” character.

And the revelation that Beau’s father is a huge penis monster locked away by his mother in their attic could have easily come straight from the mouth of Dan Lippert’s Todd Padre.

Most notably, the scene where Toni, the teenage daughter aggravated by what she sees as Beau stealing her parents’ attention away from her, encourages Beau to consume paint and eventually commits suicide by thirstily chugging down her own tin recalls a running Lounge joke involving the teachers enjoying the taste of paint and conniving schemes to cause guest characters performed by Paul F Tompkins to unknowingly ingest the stuff.

So both The Teacher’s Lounge and Beau Is Afraid dabble in the absurd with abandon, uncaring of the wider implications and uninhibited by the need for some grand unifying theory. They are stories told moment-to-moment, with the goal of torturing the protagonist(s) first and foremost in mind when making storytelling decisions. They are unconventional narratives, Kafkaesque tales of Sisyphean woe experienced by American man-children.

Approaching Beau with this comparison in mind allowed me to free myself of some of the hang-ups I’ve seen other reviewers have with the film. After all, strictly speaking there is no rule that says a film’s reality and circumstances must be more substantial or well-grounded than an improvised podcast’s. Forfeiting my desire for answers in favour of submitting to the tide freed me to enjoy Beau the way I believe it was intended. As a barrage of images and ideas, a maelstrom of paranoia and regret, a bedlam of anxiety and a riot of laughes.

Housekeeping: Thanks so much for reading! Please do let me know your thoughts, you can hit me up @primarycinema on twitter. And please do share this post/newsletter with others if you like it!