With Roxanne, Steve Martin Found A New Sincerity

or: How Steve Martin Went From A "Wild 'n' Crazy Guy" To A "Funny 'n' Relatable Actor".

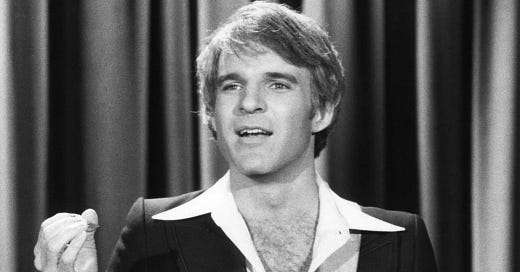

In 1987, Steve Martin’s career was at a crossroads. The seventies had seen him rise from obscurity to become the first ever comedy rockstar. He performed to sold out stadiums, was a regular SNL host, his song “King Tut” sold over one millions copies and charted on the Billboard Hot 100, and his book of short stories and essays, “Cruel Shoes” was a bestseller. But in 1979, he had a change in career, he dramatically quit stand up at the height of his success and directed all his attention towards his next conquest: Hollywood.

His debut feature film, The Jerk, was an unqualified commercial success (and even garnered the praise of Stanley Kubrick) but it was a critical clunker, leading some to theorise Martin’s popularity was merely a fad. Likely in an effort to legitimise himself as a film star, he followed up The Jerk with some more challenging roles. He took on the lead role in the Great Depression era musical drama Pennies From Heaven and had himself cannily edited into classic noir films so as to share scenes with Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in the film-noir-parody-cum-Dadaist-collage Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid.

But whilst his film work was certainly eclectic, eight years on from his breakout in The Jerk, there was still a great deal of uncertainty around Martin’s future as a leading man. Pennies and Plaid both failed at the box office, as did his mad scientist comedy The Man With Two Brains. Even Three Amigos, a film which is today considered a cult classic, failed to capture the attention of contemporary audiences. As of 1987, his most successful acting role outside of The Jerk was his scene stealing cameo as a sadistic dentist in Little Shop Of Horrors. But Martin would not be content with just cameos.

What worked on stage evidently didn’t perfectly translate to screen. He had built his popularity on absurd, formally experimental comedy. His stand up was subversive, cerebral and structurally daring. He would do crazy things like appear on The Tonight Show and perform stand up to an audience of dogs

On stage, audiences were receptive to this brand of deconstructive comedy. But sit the same audience members in a cinema as opposed to an arena, and their expectations suddenly shift. It was not enough for Martin to be funny, to survive as a Hollywood leading man, he had to be relatable. It was not enough to merely be a performer, Steve Martin had to become an actor. In short, he needed to be taken seriously. But how can you make an audience take seriously a man so steeped in irony that he became synonymous with silliness?

Well, Martin took on the challenge himself. For the first time in his career he wrote a screenplay alone — going through twenty-five rewrites over the course of three years to adapt the 19th century French play Cyrano De Bergerac into a pleasant, pastoral Hollywood romcom.

In the source text, chivalrous polymath Cyrano falls for the beautiful and intellectual Roxane but fails to pursue her romantically on account of insecurities he has about his appearance (Cyrano has a rather large nose). Roxane is meanwhile interested in the handsome but inarticulate Christian. Cyrano winds up writing love letters to Roxanne on behalf of Christian wherein he confesses all his true feelings to her through the guise of Christian.

Martin transplants the story to middle America where C.D. (Martin) is a big-nosed firefighter, the leader of the town’s volunteer fire service. He’s smart and witty, caring and kind, but his looks deprive him of the confidence to approach Roxanne (Daryl Hannah), an astronomer visiting his small town for the summer. Unaware of C.D.’s feelings, she herself becomes interested in Chris (Rick Rossovich, fresh off of “Top Gun”) the new, professional, fireman sent in to whip the town’s amateurish fire department into shape.

When Chris is crippled with nervousness and struggles to spit out even a sentence in the presence of Roxanne, C.D. feels the need to sweep in and communicate on his behalf via verbose love notes and letters.

It’s a perfect plot for a romcom, filled with sitcom level hijinks (at one point Chris wears a headset so C.D. can feed him lines as he talks to Roxanne) and calamitous misunderstandings. But it’s not just structurally sound, crucially, it is also grounded in Martin’s own lived experience.

For much of his career, Martin’s personal life was an enigma. He steadfastly refused to discuss or disclose personal relationships in interviews and preferred to either simply entertain — as he would on late night talk shows, recalling tall tales he prepared especially for each show or intellectualise — as he would often do in print interviews, discussing his work with great sophistication and introspection. He kept even innocuous parts of his private life close to his chest, such as his interest in art collecting, which he rarely ever expounded upon in much detail publicly.

As he aged, Martin loosened up a bit and now more regularly lets the veil drop. In his memoir, “Born Standing Up”, he recalls his experiences with shyness and anxiety. Long known to be reserved off stage, the book reveals him to be a tortured soul when it comes to social interactions — an unexpected revelation given his success as a flamboyant performer. Indeed, fame seemed Martin’s saving grace, he notes his notoriety aided in avoiding such unpleasant exercises as icebreaker introductions.

As his fame grew, he would regularly experience panic attacks. Dark, gloomy descents of anxiety that filled him with terror. He kept these symptoms private and learned to compartmentalise these parts of himself so he could “be a comedy writer, be a stand-up comedian and endure private mortal fear.”

His contemporaries paint Martin as an incredibly bashful presence off stage, never one to draw attention to himself. He instead seems most comfortable in the role of an observer — far from the personality we see on stage and screen. Martin has since gone on to examine this side of himself in more detail in his literary fiction such as in his novel The Pleasure of my Company.

But Roxanne came before these revelations and, in retrospect, the film appears to be the first time Martin confronted this personal contradiction and investigated his social anxieties. I can’t help but draw connections between Martin, the timid, soft spoken specimen of a man who, somewhat paradoxically, can stand on a stage before thousands of strangers and act like a total doofus — and C.D., the clever, gentle soul who can’t bear to relate his affections to Roxanne in person but whom, when putting pen to paper, can become a grandiose poet, endlessly waxing rhapsodic about her innumerable qualities.

Whereas his previous comedies relied primarily on absurdist situations , whacky behaviour and larger than life characters, Roxanne is built upon a strong emotional and romantic foundation. Before this, Martin’s stand-up and comedy film careers were drenched in irony but, in Roxanne, he practices restraint. As C.D. declares ten minutes into the film, “Oh, irony! We don’t get that down here!”.

While the film is of course not nearly irony free, it does mark the first time Martin, previously just a master formalist, turned his attention inward and reckoned with his own demons. His previous comedy films (especially his work with director Carl Reiner) were mostly interested in subverting genre conventions and parodying more earnest material. They were almost analytical in their construction, products of logic rather than emotion. But with Roxanne, he dared to be sincere. No more is this sincerity on display than when C.D. confides in his friend Dixie (Shelley Duvall), about his insecurities regarding his appearance;

“You know, sometimes I walk around this town at night and I see couples walking along, holding hands. And I look at them and I think, eh, why not me? And then, uh, I catch my shadow on the wall.”

The dialogue is heartfelt and grounded, it doesn’t sell out it’s earnestness for a cheap laugh. It merely exists to communicate the character’s internal struggle. It’s Steve Martin being serious.

But it’s not Steve Martin being unfunny. Naturally, there are still the signature goofy bits the audience expects from Martin, C.D. entering the town’s firehouse to see a trashcan on fire and roaring to his underlings, “god damn it, we’re supposed to put them OUT.” is a personal favourite, but the comedic scenes are complimented by ones exhibiting genuine human connection and pathos.

The large prosthetic nose Martin wears helps deflate some of his earnestness. The prosthetic recalls the plastic-arrow-through-the-head he made famous on stage and he wields it as both a crutch and a weapon. Martin can deliver solemn lines such as those above whilst still gainfully mining the feature for comedic bits, a job he carries out dutifully.

The nose bits range from Martin politely snorting a glass of wine, to reciting twenty nose-centric insults to upstage a thug at a local bar. Ranging from the childish “excuse me, is that your nose or did a bus park on your face” to the oblique “boy, I’d hate to see the grindstone”, C.D. lists off cruel but hilarious taunts, making himself a spectacle for the entire bar to gawk at and laugh along with.

The bar monologue is akin to stand up, it allows Martin to do what he does best. But here the comedy it’s delivered with the benefit of emotional context. In the scene, C.D. is exhibiting a learned behaviour he has adopted to get by, he is quick and witty (traits Roxanne falls for) because he feels the need to outdo his bullies. In the scene, we learn a fundamental truth about C.D.’s character, that his intellectualism and wit is a defence mechanism honed to subdue his adversaries. Whereas previous Martin character found their laughs through pastiche and parody, here he transcends the silly and delivers the sincere.

An earlier scene sees C.D. serve as a companion to a young school boy who climbed up on the roof of his house and refused to come down. Martin takes the opportunity to veer away from over-the-top silly gags and focuses on strong character work instead. C.D. sympathises with the boy, who is being bullied in school because of his weight. The scene ends when the kid asks if he has to get down. C.D. shakes his head, “No, no, let’s just stay up here for a while.” The two sit there and enjoy the view, far away from judging eyes. It’s quiet moments like this that breathe humanity into the film.

Earlier in his career, Martin may have avoided potentially saccharine scenes such as that one. His willingness to adapt and facilitate emotional story beats into his comedies shows great maturity and self-awareness. Indeed, this change in Martin’s career trajectory can even be compared to the New Sincerity art movement which went on to flourish in the nineties and noughties.

New Sincerity practitioners rejected postmodernist irony and cynicism, instead choosing to embrace sincere, emotionally charged work. This almost perfectly describes Martin’s development as an artist -- from bursting onto the scene as a deconstructive, gleefully experimental stand-up comedian who routinely poked fun at the very concept of performance itself, to evolving into a fearlessly schmaltzy (when called for) movie star.

With Roxanne, Steve Martin became not just funny but also lovable. And it served as the model for Martin’s future projects, a classic goofball comedy complete with the requisite humour, gags and yes, irony, but these elements were built on a strong emotional core. Portions of this alchemy can be seen throughout his later filmography, whether it be in Parenthood or It’s Complicated, Father Of The Bride or Cheaper By The Dozen. With Roxanne, Martin moved beyond performance and began to act.

Housekeeping

Hey folks. Thank you very, very much for subscribing to my Substack. I hope you enjoyed the above essay on Steve Martin — it’s the product of a lengthy obsession with him of mine. And that obsession isn’t going to stop anytime soon, he has a new book due out later this year, a memoir focusing on his film career. So when I get my hands on that I’ll be sure to write a follow up newsletter to let you know my thoughts.

I intend on getting another essay out on either Monday or Tuesday next week. But I’m also starting a new job then so please forgive me if my schedule is a little unpredictable for the next little while.

And hey, if you liked this post, sharing it on social media would be a big help as I try and get this newsletter off the ground. Tell all your pals — primarycinema.substack.com is the place to be!

Thanks for everything,

Gavin